Page 81 - JSOM Fall 2025

P. 81

Esophageal Perforation Following Explosive Injury

A Case Report

Stevan C. Fairburn, BS *; Emily W. Baird, MD ; Michelle Mangold, DO ;

1

2

3

Michael F. Gleason, MD ; James M. Donahue, MD ; Ali M. Ahmed, MD ; John B. Holcomb, MD 7

6

4

5

ABSTRACT

Esophageal perforations, though rare, are critical injuries be- accidents, falls, explosions, and stab or gunshot wounds. 1,7,8

cause of the risk of rapid progression to mediastinitis and sep- The complexity of traumatic perforations often leads to de-

sis. Traumatic perforations, especially those following blunt layed diagnosis and intervention (>24 hours), further increas-

trauma, carry high mortality, and explosive injuries may cause ing the risk of severe complications and mortality. 9,10 The

such damage. Here, we describe the case of a 38-year-old male anatomical location of esophageal perforations can vary, with

with a history of opioid use disorder and hepatitis C who suf- thoracic perforations being the most prevalent, followed by

fered a mid-esophageal perforation after a pressurized diesel cervical and abdominal locations. This distribution is signifi-

fuel cap exploded, hitting his face. He presented with intraoral cant, as the location of the perforation influences the clinical

burns, chest pain, subcutaneous emphysema, and pneumome- presentation and management strategy. 9,10

diastinum. Endoscopic evaluation confirmed the perforation,

and he was successfully treated with esophageal stenting and Early identification and appropriate intervention are critical,

IV antibiotics. Follow-up imaging showed no persistent leak, as delays in treatment are associated with significantly higher

and he was discharged with plans for stent removal. This case morbidity and mortality. Although there is a significant body

2,3

highlights the importance of considering esophageal injury in of literature describing traumatic esophageal perforations,

explosive trauma and suggests that while endoscopic manage- there are only a handful of cases describing esophageal perfo-

ment is effective, operative readiness is crucial in resource- rations after an explosive injury.

limited and military settings, where explosive trauma is more

common.

Case Presentation

Keywords: esophageal perforation; explosive injury; trauma; Here we describe the case of a 38-year-old male with a his-

endoscopic stent tory of opioid use disorder and active hepatitis C virus (HCV)

infection who was admitted as a level 1 trauma patient after

a pressurized cap to a diesel fuel tank exploded, striking him

in the face. Upon arrival, the primary survey revealed an in-

Introduction

tact airway, bilateral equal breath sounds, palpable femoral

Esophageal perforations are rare yet serious injuries due to the pulses, a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15, and 2mm

potentially rapid progression to mediastinitis and sepsis. This reactive pupils. Secondary assessment noted deep bilateral lip

rapid progression is primarily a result of esophageal contents lacerations extending to the corners of his mouth and intra-

leaking into the surrounding mediastinal and pleural spaces, oral burns. Initial chest x-ray revealed extensive subcutaneous

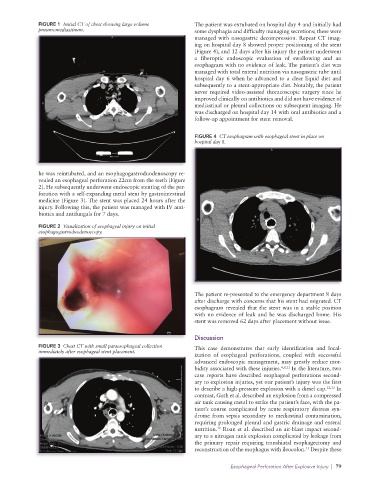

leading to severe inflammation, infection, and mediastinitis. 1 emphysema in the lower neck and mediastinum and a large

Esophageal injuries have reported mortality rates ranging volume pneumomediastinum on initial chest CT (Figure 1).

from 10% to 40%, with early recognition and intervention The patient was intubated for airway protection.

(<24 hours) key to reducing morbidity and mortality. 2–5 Typ-

ically, esophageal injuries are managed surgically, and more The lacerations were repaired, bronchoscopy was performed,

recently endoscopically. Traumatic esophageal perforations, and the patient was extubated with plans for CT esophagram

5–7

although less common, are significant because of their associ- which was ultimately impossible given ongoing dysphagia.

ation with other severe injuries. These perforations can result Direct laryngoscopy revealed scattered burns and increased

from both blunt and penetrating trauma, such as motor vehicle swelling at the posterior oropharynx. Given these findings,

*Correspondence to scfairbu@uab.edu

1 Stevan C. Fairburn is affiliated with the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, Marnix E. Heersink Institute

for Biomedical Innovation, Birmingham, AL. Dr. Emily W. Baird is affiliated with the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School

2

7

of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Birmingham, AL. Dr. Michelle Mangold and Dr. John B. Holcomb are affiliated with the University of

3

Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, Department of Surgery, Division of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, Birmingham, AL.

5

4 Dr. Michael F. Gleason and Dr. James M. Donahue are affiliated with the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine,

Department of Surgery, Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Birmingham, AL. Dr. Ali M. Ahmed is affiliated with the University of Alabama at

6

Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Birmingham, AL.

78