Page 66 - JSOM Fall 2024

P. 66

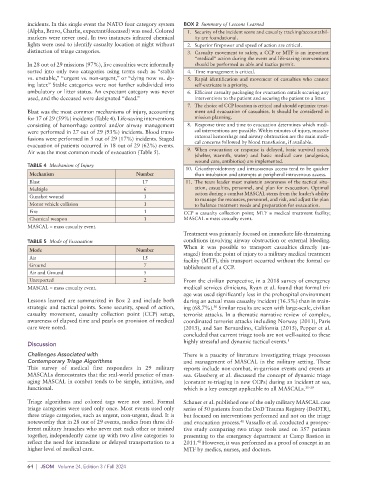

incidents. In this single event the NATO four category system BOX 2 Summary of Lessons Learned

(Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, expectant/deceased) was used. Colored 1. Security of the incident scene and casualty tracking/accountabil-

markers were never used. In two instances infrared chemical ity are foundational.

lights were used to identify casualty location at night without 2. Superior firepower and speed of action are critical.

distinction of triage categories. 3. Casualty movement to safety, a CCP or MTF is an important

“medical” action during the event and life-saving interventions

In 28 out of 29 missions (97%), live casualties were informally should be performed as able and tactics permit.

sorted into only two categories using terms such as “stable 4. Time management is critical.

vs. unstable,” “urgent vs. non-urgent,” or “dying now vs. dy- 5. Rapid identification and movement of casualties who cannot

ing later.” Stable categories were not further subdivided into self-extricate is a priority.

ambulatory or litter status. An expectant category was never 6. Efficient casualty packaging for evacuation entails securing any

used, and the deceased were designated “dead.” interventions to the patient and securing the patient to a litter.

7. The choice of CCP location is critical and should optimize treat-

Blast was the most common mechanisms of injury, accounting ment and evacuation of casualties. It should be considered in

for 17 of 29 (59%) incidents (Table 4). Life-saving interventions mission planning.

consisting of hemorrhage control and/or airway management 8. Response time and time to evacuation determines which medi-

were performed in 27 out of 29 (93%) incidents. Blood trans- cal interventions are possible. Within minutes of injury, massive

fusions were performed in 5 out of 29 (17%) incidents. Staged external hemorrhage and airway obstruction are the main medi-

evacuation of patients occurred in 18 out of 29 (62%) events. cal concerns followed by blood transfusion, if available.

Air was the most common mode of evacuation (Table 5). 9. When evacuation or response is delayed, basic survival needs

(shelter, warmth, water) and basic medical care (analgesics,

wound care, antibiotics) are implemented.

TABLE 4 Mechanism of Injury

10. Cricothyroidotomy and intraosseous access tend to be quicker

Mechanism Number than intubation and attempts at peripheral intravenous access.

Blast 17 11. The team leader must maintain awareness of the tactical situ-

Multiple 6 ation, casualties, personnel, and plan for evacuation. Optimal

action during a combat MASCAL stems from the leader’s ability

Gunshot wound 3 to manage the resources, personnel, and risk, and adjust the plan

Motor vehicle collision 1 to balance treatment needs and preparation for evacuation.

Fire 1 CCP = casualty collection point; MTF = medical treatment facility;

Chemical weapon 1 MASCAL = mass casualty event.

MASCAL = mass casualty event.

Treatment was primarily focused on immediate life-threatening

TABLE 5 Mode of Evacuation conditions involving airway obstruction or external bleeding.

When it was possible to transport casualties directly (un-

Mode Number staged) from the point of injury to a military medical treatment

Air 15 facility (MTF), this transport occurred without the formal es-

Ground 7 tablishment of a CCP.

Air and Ground 5

Unreported 2 From the civilian perspective, in a 2018 survey of emergency

MASCAL = mass casualty event. medical services clinicians, Ryan et al. found that formal tri-

age was used significantly less in the prehospital environment

Lessons learned are summarized in Box 2 and include both during an actual mass casualty incident (16.3%) than in train-

strategic and tactical points. Scene security, speed of action, ing (68.7%). Similar results are seen with large-scale, civilian

30

casualty movement, casualty collection point (CCP) setup, terrorist attacks. In a thematic narrative review of complex,

awareness of elapsed time and pearls on provision of medical coordinated terrorist attacks including Norway (2011), Paris

care were noted. (2015), and San Bernardino, California (2015), Pepper et al.

concluded that current triage tools are not well-suited to these

Discussion highly stressful and dynamic tactical events. 1

Challenges Associated with There is a paucity of literature investigating triage processes

Contemporary Triage Algorithms and management of MASCAL in the military setting. These

This survey of medical first responders in 29 military reports include non-combat, in-garrison events and events at

MASCALs demonstrates that the real-world practice of man- sea. Glassberg et al. discussed the concept of dynamic triage

aging MASCAL in combat tends to be simple, intuitive, and (constant re-triaging in new CCPs) during an incident at sea,

functional. which is a key concept applicable to all MASCALs. 35–39

Triage algorithms and colored tags were not used. Formal Schauer et al. published one of the only military MASCAL case

triage categories were used only once. Most events used only series of 50 patients from the DoD Trauma Registry (DoDTR),

three triage categories, such as urgent, non-urgent, dead. It is but focused on interventions performed and not on the triage

noteworthy that in 28 out of 29 events, medics from three dif- and evacuation process. Vassallo et al. conducted a prospec-

40

ferent military branches who never met each other or trained tive study comparing two triage tools used on 357 patients

together, independently came up with two alive categories to presenting to the emergency department at Camp Bastion in

reflect the need for immediate or delayed transportation to a 2011. However, it was performed as a proof of concept in an

41

higher level of medical care. MTF by medics, nurses, and doctors.

64 | JSOM Volume 24, Edition 3 / Fall 2024