Page 49 - JSOM Fall 2023

P. 49

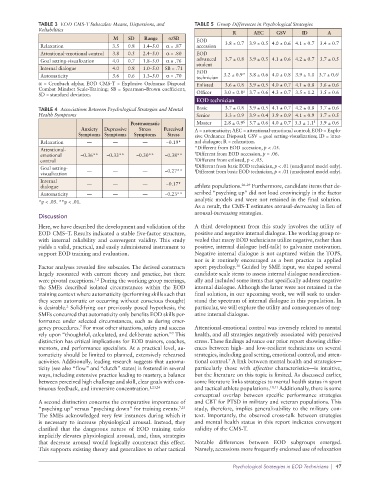

TABLE 3 EOD CMS-T Subscales: Means, Dispersions, and TABLE 5 Group Differences in Psychological Strategies

Reliabilities

R AEC GSV ID A

M SD Range α/SB EOD

Relaxation 3.5 0.8 1.4–5.0 α = .87 accession 3.8 ± 0.7 3.9 ± 0.5 4.0 ± 0.6 4.1 ± 0.7 3.4 ± 0.7

Attentional-emotional control 3.8 0.5 2.4–5.0 α = .80 EOD

Goal setting-visualization 4.0 0.7 1.8–5.0 α = .76 advanced 3.7 ± 0.8 3.9 ± 0.5 4.1 ± 0.6 4.2 ± 0.7 3.7 ± 0.5

student

Internal dialogue 4.0 0.8 1.0–5.0 SB = .71

EOD †

Automaticity 3.6 0.6 1.3–5.0 α = .70 technician 3.2 ± 0.9* 3.8 ± 0.6 4.0 ± 0.8 3.9 ± 1.0 3.7 ± 0.6

α = Cronbach alpha; EOD CMS-T = Explosive Ordnance Disposal Enlisted 3.6 ± 0.8 3.9 ± 0.5 4.0 ± 0.7 4.1 ± 0.8 3.6 ± 0.6

Combat Mindset Scale-Training; SB = Spearman–Brown coefficient; ‡

SD = standard deviation. Officer 3.0 ± 0.8 3.7 ± 0.6 4.3 ± 0.7 3.5 ± 1.2 3.5 ± 0.6

EOD technician

TABLE 4 Associations Between Psychological Strategies and Mental Basic 3.7 ± 0.8 3.9 ± 0.5 4.1 ± 0.7 4.2 ± 0.8 3.7 ± 0.6

Health Symptoms Senior 3.3 ± 0.9 3.9 ± 0.4 3.9 ± 0.9 4.1 ± 0.9 3.7 ± 0.5

Posttraumatic Master 2.8 ± 0.9 § 3.7 ± 0.6 4.0 ± 0.7 3.3 ± 1.1 || 3.9 ± 0.6

Anxiety Depressive Stress Perceived A = automaticity; AEC = attentional-emotional control; EOD = Explo-

Symptoms Symptoms Symptoms Stress sive Ordnance Disposal; GSV = goal setting-visualization; ID = inter-

Relaxation — — — −0.19* nal dialogue; R = relaxation.

Attentional- *Different from EOD accession, p < .05.

emotional −0.36** −0.33** −0.30** −0.38** † Different from EOD accession, p = .06.

control ‡ Different from enlisted, p < .05.

§ Different from basic EOD technician, p < .01 (unadjusted model only).

Goal setting- ||

visualization — — — −0.27** Different from basic EOD technician, p < .01 (unadjusted model only).

Internal — — — −0.17*

dialogue athlete populations. 26–29 Furthermore, candidate items that de-

Automaticity — — — −0.23** scribed “psyching up” did not load convincingly in the factor

*p < .05. **p < .01. analytic models and were not retained in the final solution.

As a result, the CMS-T estimates arousal-decreasing in lieu of

arousal-increasing strategies.

Discussion

Here, we have described the development and validation of the A third development from this study involves the utility of

EOD CMS–T. Results indicated a stable five-factor structure, positive and negative internal dialogue. The working group re-

with internal reliability and convergent validity. This study vealed that many EOD technicians utilize negative, rather than

yields a valid, practical, and easily administered instrument to positive, internal dialogue (self-talk) to galvanize motivation.

support EOD training and evaluation. Negative internal dialogue is not captured within the TOPS,

nor is it routinely encouraged as a best practice in applied

Factor analyses revealed five subscales. The derived constructs sport psychology. Guided by SME input, we shaped several

30

largely resonated with current theory and practice, but there candidate scale items to assess internal dialogue nondirection-

were pivotal exceptions. During the working group meetings, ally and included some items that specifically address negative

1,2

the SMEs described isolated circumstances within the EOD internal dialogue. Although the latter were not retained in the

training context where automaticity (performing skills such that final solution, in our upcoming work, we will seek to under-

they seem automatic or occurring without conscious thought) stand the spectrum of internal dialogue in this population. In

is desirable. Solidifying our previously posed hypothesis, the particular, we will explore the utility and consequences of neg-

2

SMEs concurred that automaticity only benefits EOD skills per- ative internal dialogue.

formance under selected circumstances, such as during emer-

gency procedures. For most other situations, safety and success Attentional-emotional control was inversely related to mental

7

rely upon “thoughtful, calculated, and deliberate action.” This health, and all strategies negatively associated with perceived

7

distinction has critical implications for EOD trainers, coaches, stress. These findings advance our prior report showing differ-

mentors, and performance specialists. At a practical level, au- ences between high- and low-resilient technicians on several

tomaticity should be limited to planned, extensively rehearsed strategies, including goal setting, emotional control, and atten-

7

activities. Additionally, leading research suggests that automa- tional control. A link between mental health and strategies—

ticity (see also “flow” and “clutch” states) is fostered in several particularly those with affective characteristics—is intuitive,

ways, including extensive practice leading to mastery, a balance but the literature on this topic is limited. As discussed earlier,

between perceived high challenge and skill, clear goals with con- some literature links strategies to mental health status in sport

tinuous feedback, and immersive concentration. 1,23,24 and tactical athlete populations. 10,11 Additionally, there is some

conceptual overlap between specific performance strategies

A second distinction concerns the comparative importance of and CBT for PTSD in military and veteran populations. This

“psyching up” versus “psyching down” for training events. 7,25 study, therefore, implies generalizability to the military con-

The SMEs acknowledged very few instances during which it text. Importantly, the observed cross-talk between strategies

is necessary to increase physiological arousal. Instead, they and mental health status in this report indicates convergent

clarified that the dangerous nature of EOD training tasks validity of the CMS-T.

implicitly elevates physiological arousal, and, thus, strategies

that decrease arousal would logically counteract this effect. Notable differences between EOD subgroups emerged.

This supports existing theory and generalizes to other tactical Namely, accessions more frequently endorsed use of relaxation

Psychological Strategies in EOD Technicians | 47