Page 17 - JSOM Summer 2023

P. 17

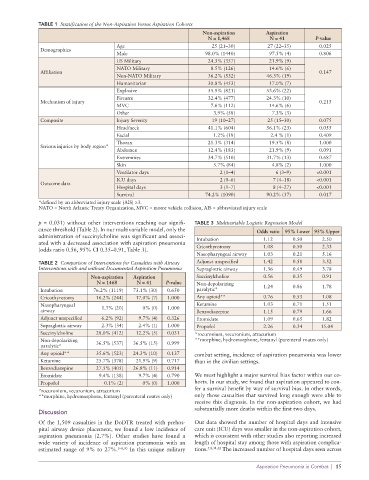

TABLE 1 Stratification of the Non-Aspiration Versus Aspiration Cohorts

Non-aspiration Aspiration

N = 1,468 N = 41 P-value

Age 25 (21–30) 27 (22–35) 0.025

Demographics

Male 98.0% (1440) 97.5% (4) 0.806

US Military 24.3% (357) 21.9% (9)

NATO Military 8.5% (126) 14.6% (6)

Affiliation 0.147

Non-NATO Military 36.2% (532) 46.3% (19)

Humanitarian 30.8% (453) 17.0% (7)

Explosive 55.9% (821) 53.6% (22)

Firearm 32.4% (477) 24.3% (10)

Mechanism of injury 0.215

MVC 7.6% (112) 14.6% (6)

Other 3.9% (58) 7.3% (3)

Composite Injury Severity 19 (10–27) 25 (15–30) 0.075

Head/neck 41.1% (604) 56.1% (23) 0.055

Facial 1.2% (18) 2.4 % (1) 0.409

Thorax 21.3% (314) 19.5% (8) 1.000

Serious injuries by body region*

Abdomen 12.4% (183) 21.9% (9) 0.091

Extremities 34.7% (510) 31.7% (13) 0.687

Skin 5.7% (84) 4.8% (2) 1.000

Ventilator days 2 (1–4) 6 (3–9) <0.001

ICU days 2 (0–6) 7 (4–18) <0.001

Outcome data

Hospital days 3 (1–7) 8 (4–27) <0.001

Survival 74.2% (1090) 90.2% (37) 0.017

*defined by an abbreviated injury scale (AIS) ≥3.

NATO = North Atlantic Treaty Organization, MVC = motor vehicle collision, AIS = abbreviated injury scale

p = 0.031) without other interventions reaching our signifi- TABLE 3 Multivariable Logistic Regression Model

cance threshold (Table 2). In our multivariable model, only the Odds ratio 95% Lower 95% Upper

administration of succinylcholine was significant and associ- Intubation 1.12 0.50 2.50

ated with a decreased association with aspiration pneumonia

(odds ratio 0.56, 95% CI 0.35–0.91, Table 3). Cricothyrotomy 1.08 0.50 2.33

Nasopharyngeal airway 1.03 0.21 5.16

TABLE 2 Comparison of Interventions for Casualties with Airway Adjunct unspecified 1.42 0.58 3.52

Interventions with and without Documented Aspiration Pneumonia Supraglottic airway 1.36 0.49 3.78

Non-aspiration Aspiration Succinylcholine 0.56 0.35 0.91

N = 1468 N = 41 P-value Non-depolarizing 1.24 0.86 1.78

Intubation 76.2% (1119) 73.1% (30) 0.650 paralytic*

Cricothyrotomy 16.2% (244) 17.0% (7) 1.000 Any opioid** 0.76 0.53 1.08

Nasopharyngeal 1.3% (20) 0% (0) 1.000 Ketamine 1.03 0.71 1.51

airway Benzodiazepine 1.15 0.79 1.66

Adjunct unspecified 6.2% (92) 9.7% (4) 0.326 Etomidate 1.09 0.65 1.82

Supraglottic airway 2.3% (34) 2.4% (1) 1.000 Propofol 2.26 0.34 15.04

Succinylcholine 28.0% (412) 12.2% (5) 0.031 *rocuronium, vecuronium, atracurium

Non-depolarizing **morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl (parenteral routes only)

paralytic* 36.5% (537) 36.5% (15) 0.999

Any opioid** 35.6% (523) 24.3% (10) 0.137 combat setting, incidence of aspiration pneumonia was lower

Ketamine 25.7% (378) 21.9% (9) 0.717 than in the civilian settings.

Benzodiazepine 27.5% (405) 26.8% (11) 0.914

Etomidate 9.4% (138) 9.7% (4) 0.790 We must highlight a major survival bias factor within our co-

Propofol 0.1% (2) 0% (0) 1.000 horts. In our study, we found that aspiration appeared to con-

*rocuronium, vecuronium, atracurium fer a survival benefit by way of survival bias. In other words,

**morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl (parenteral routes only) only those casualties that survived long enough were able to

receive this diagnosis. In the non-aspiration cohort, we had

substantially more deaths within the first two days.

Discussion

Of the 1,509 casualties in the DoDTR treated with prehos- Our data showed the number of hospital days and intensive

pital airway device placement, we found a low incidence of care unit (ICU) days was smaller in the non-aspiration cohort,

aspiration pneumonia (2.7%). Other studies have found a which is consistent with other studies also reporting increased

wide variety of incidence of aspiration pneumonia with an length of hospital stay among those with aspiration complica-

estimated range of 9% to 27%. 5–8,30 In this unique military tions. 5,8,31,32 The increased number of hospital days seen across

Aspiration Pneumonia in Combat | 15