Page 58 - JSOM Fall 2019

P. 58

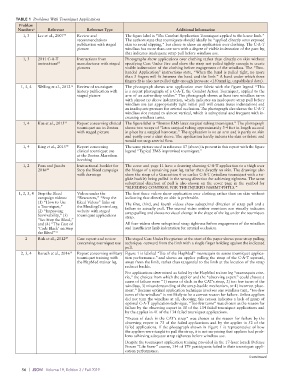

TABLE 1 Problems With Tourniquet Applications

Problem

Numbers Reference Reference Type Additional Information

a

1, 3 Lee et al., 2007 15 Review and The figure label is “The Combat Application Tourniquet applied to the lower limb.”

recommendations The authors state that tourniquets should ideally be “applied directly onto exposed

publication with staged skin to avoid slipping,” but chose to show an application over clothing. The C-A-T

picture windlass has more than one turn with a degree of visible indentation of the pant leg

that indicates inadequate strap pull before windlass use.

1, 3 2011 C-A-T Instructions from Photographs show applications over clothing rather than directly on skin without

instructions 65 manufacturer with staged specifying Care Under Fire and show the strap not pulled tightly enough to create

pictures visible indentation of the clothing before engagement of the windlass. The “Two-

handed Application” instructions state, “When the band is pulled tight, no more

than 3 fingers will fit between the band and the limb.” A band under which three

fingers fit is also not pulled tight enough (pressure <150mmHg, unpublished data).

1, 3, 4 Welling et al., 2012 16 Review of tourniquet The photograph shows arm application over fabric with the figure legend “This

history publication with is a recent photograph of a C-A-T, the Combat Action Tourniquet, applied to the

staged picture arm of an active-duty soldier.” The photograph shows at least two windlass turns

with almost no sleeve indentation, which indicates an inadequate strap pull before

windlass use (an appropriately tight initial pull will create tissue indentation) and

an inadequate pressure for arterial occlusion. The photograph also shows the C-A-T

windlass slot rotated to almost vertical, which is suboptimal and frequent with in-

creasing windlass turns.

1, 4 Kue et al., 2015 17 Report concerning clinical The figure label is “Boston EMS latex surgical tubing tourniquet.” The photograph

tourniquet use in Boston shows two wraps of “latex surgical tubing approximately 3-4 feet in length secured

with staged picture in place by a surgical hemostat.” The application is on an arm and is partly on skin

and partly over a shirt sleeve. The application hardly indents the skin or fabric and

would not stop arterial flow.

1, 4 King et al., 2015 18 Report concerning The same picture used in reference 17 (above) is present in this report with the figure

clinical tourniquet use legend “Typical EMS improvised tourniquet.”

at the Boston Marathon

bombing

1, 2 Pons and Jacobs Instructional booklet for The cover and page 11 have a drawing showing C-A-T application to a thigh over

2016 42 Stop the Bleed campaign the fringes of a remaining pant leg rather than directly on skin. The drawings also

with drawings show the strap of a Generation 6 or earlier C-A-T (windlass tourniquet with a tri-

glide buckle) being pulled in the wrong direction for achieving tightness. The same

sub optimal direction of pull is also shown on the cover page in the symbol for

“BLEEDING CONTROL FOR THE INJURED NAEMT-PHTLS.”

1, 2, 3, 4 Stop the Bleed Videos under the The first three videos show application over clothing rather than on skin without

campaign videos: “Resources,” “Stop the indicating that directly on skin is preferable.

(1) “How to Use Bleed Videos” links on The first, third, and fourth videos show suboptimal direction of strap pull and a

a Tourniquet,” the BleedingControl.org failure to actually pull. The second video neither mentions nor visually indicates

(2) “Improving website with staged strap pulling and shows no visual change in the shape of the leg under the tourniquet

Survivability,” (3) tourniquet applications strap.

“See Stop the Bleed,”

and (4) “The Cast of All four videos show suboptimal strap tightness before engagement of the windlass

‘Code Black’ on Stop and insufficient limb indentation for arterial occlusion.

the Bleed” 31

2 Risk et al., 2012 29 Case report and review The staged Care Under Fire picture at the start of the paper shows poor strap pulling

concerning tourniquet use technique: outward from the limb with a single finger holding against the indicated

pull.

2, 3, 4 Baruch et al., 2016 19 Report concerning military Figure 1 is labeled “Use of the HapMed mannequin to assess tourniquet applica-

™

tourniquet training with tion performance.” and shows an applier pulling the strap of the C-A-T upward,

the HapMed trainer leg away from the limb, rather than tangential to the limb at the location of the strap

redirect buckle.

For applications determined as failed by the HapMed trainer leg “mannequin crite-

ria,” the choices from which the applier and the “observing expert” could choose a

cause of failure were “1) excess of slack in the CAT’s strap, 2) too few turns of the

windlass, 3) misunderstanding of the strap-buckle mechanism, or 4) incorrect place-

ment.” Because optimal application technique involves one windlass turn, “too few

turns of the windlass” is not likely to be a correct reason for failure. Unless appliers

did not turn the windlass at all, choosing this reason indicates a lack of grasp of

optimal C-A-T application technique. “Too few turns” was chosen as the reason for

failure by the observing expert in 30 of the 134 failed tourniquet applications and

by the applier in 41 of the 134 failed tourniquet applications.

“Excess of slack in the CAT’s strap” was chosen as the reason for failure by the

observing expert in 73 of the failed applications and by the applier in 52 of the

failed applications. If the photograph shown in Figure 1 is representative of how

the appliers were taught to pull the strap, it is not surprising that appliers had prob-

lems achieving adequate strap tightness before windlass use.

Despite the tourniquet application training provided in the 17-hour Israeli Defense

Forces “Life Saver” course, 134 of 179 participants failed in their tourniquet appli-

cation performance.

(continues)

56 | JSOM Volume 19, Edition 3 / Fall 2019